by Professor Richard Bolden

- 18 January 2024

Share:

I have spent the past two and a half decades working as a leadership researcher and educator in UK universities. Throughout much of this time I have studied leadership in higher education (HE) as well as experiencing it first-hand. I have taken on leadership roles — both formal and informal — and have witnessed the trials and tribulations of colleagues as they have endeavoured to navigate the complexities of this context. In this article I share reflections on what I have learnt, why it matters, and what we can (all) do to enhance the quality and inclusiveness of leadership in this important sector.

Why Higher Education Leadership Matters

To begin it’s worth considering why HE matters for leadership theory, practice, and development. My own interest in researching leadership in this context was sparked by early work on distributed leadership in schools (e.g., Gronn, 2003; Spillane et al., 2004). HE provided an obvious testbed for exploring how such ideas might apply to other educational settings — particularly those with more complex structures, cultures, identities, and performance outcomes. Although there is fairly widespread agreement that the key purpose of effective school leadership is to improve pupil outcomes (Leithwood et al., 2006), the same does not apply to universities. Whilst student outcomes are undoubtably important metrics — and if you are a student, parent, or potential employer, perhaps the ones that concerns you most — this is not the only criterion by which HE institutions (and their staff) are evaluated. Another essential area of activity for universities is research — typically assessed in terms of “high quality” publications as well as by the volume of funding secured. Alongside this are agendas for external engagement and impact, not to mention the very real concerns of keeping universities running as viable businesses. Together, the diversity of stakeholders and priorities in HE produces a complex and contested environment where people and organizations may feel pulled in different directions. Such issues are not unique to HE but do make it an interesting context in which to study leadership, with important insights for emerging areas of scholarship, including complexity leadership (Uhl Bien, 2021), paradoxical leadership (Smith, et al., 2016) and collective leadership (Ospina et al., 2020).

At the center of any analysis of leadership is the interconnection between purpose, values, and identity, yet the somewhat schizophrenic nature of academia disrupts these dynamics in ways that can produce a sense of disenchantment, disengagement, and alienation. The HE system (in the UK and elsewhere) is founded on competing values systems — emphasizing both normative aspects (such as public service, professional autonomy, collegial practice, and traditions) and utilitarian principles (such as profit-making, corporate management, customer service, and change), such that a university “considers itself (and others consider it), alternatively, or even simultaneously, to be different types of organisations” (Albert & Whetten, 1985, p. 270).

The hybrid nature of HE poses particular challenges for leaders trying to establish credibility and legitimacy in the eyes of those they seek to influence, as different stakeholders identify “more with members of their own subcultures rather than as members of the university” (Winter & O’Donohue, 2012, p. 566). This is particularly true of academics who, as knowledge workers, carry professional identities and affiliations that extend well beyond their immediate employer. Whilst these, and other factors, make HE a particularly rich and rewarding context in which to study leadership there remains surprisingly little robust empirical research in this area and the HE leadership literature tends to be fragmented according to the perspectives and ideologies of different groups (Macfalane, et al., 2024).

Crisis, What Crisis?

The conceptual complexities of leadership in HE may, in part, help explain some of the difficulties facing the sector. Universities were particularly hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic (PWC, 2021) and whilst the immediate crisis may have passed, it has exposed deep-seated issues that have (by and large) remained below the surface for many years. In particular, accounts of “toxic” management are linked to widescale dissatisfaction, industrial action, and recruitment challenges in the sector (Watermeyer et al., 2021).

In a series of focus groups conducted as part of a project for Advance HE in Sept-Dec 2021 colleagues and I asked participants about the shifting context of global higher education (Watermeyer et al., 2022). Five key areas — policy, society, funding, students, and staff — were highlighted as impacting perceptions, experiences, and practices of leadership in contemporary HE. While the specifics of contextual issues varied between institutions and countries, there was strong agreement across the groups that current changes are producing tensions and challenges that are hard to resolve, as outlined in the following quote from a participant in Roundtable 1 with Heads of Departments and Deans.

“What we've seen… is this need [to]be agile and really responding to what is happening, straight now, but at the same time be someone who is looking ahead, at the same time as somebody who has that emotional intelligence to deal with not only their student population who is changing dramatically, but the needs of our staff and our whole pedagogy is changing? What do leaders need to do? How do they need to act? How do they need to be?” (p. 27).

In Britain, declining numbers of international students are putting huge pressures on a funding system dictated by government such that a third of universities are estimated to be trading at a deficit (Jenkins, 2023). In such circumstances it is hardly surprising that “bottom-line” financial performance metrics are of primary concern to senior institutional leaders, as are ranking schemes that determine the relative attractiveness of institutions to potential students.

Such measures, however, tend to be of far less significance to academics themselves in terms of what motivates and inspires them to work in HE. The growing divide between academics and managers is reported to be fueling extensive discontent within the sector, as indicated by unprecedented levels of industrial action across the UK (and elsewhere) throughout 2023 and reports of a “great resignation” (Ross, 2022).

Follower Perspectives on Leadership in Higher Education

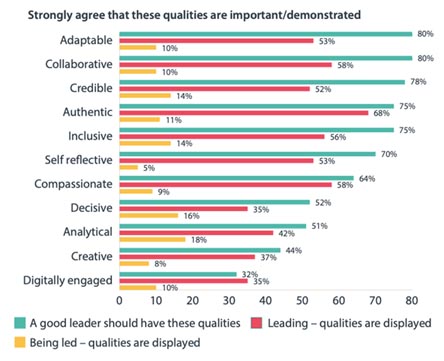

Within the Advance HE scoping study mentioned earlier, participants were asked to identify “what new or future leadership skills/competencies/behaviours are required within your organisation, professional area and/or wider sector?” Thematic coding identified 11 categories, which were incorporated into a subsequent survey completed by 553 respondents from around the World (Neves & Parkin, 2023). Figure 1 shows the proportion of respondents who strongly agreed that these qualities were important for good leaders within HE, as well as the extent to which they felt they demonstrated these qualities themselves (when leading) or observed these qualities within the people they were expected to follow (being led).

Figure 1 – Chart based on those who “agree strongly” with each statement — the top point on a five-point agreement scale. Ranked in order of whether a good leader should have these qualities (Neves & Parkin, 2023: 9) [Reproduced with permission from Advance HE]

There is a clear pattern within the data, whereby good HE leaders are expected to be adaptable, collaborative, credible, authentic, inclusive, and self-reflective (with compassion also ranked highly). Participants rated their own capacity moderately highly on each of these qualities (albeit it consistently lower than the ideal). The most striking finding from this graph, however, is the huge gap between each of these rankings and perceptions of those people currently in leadership roles.

Follower perspectives (“being led”) suggest a gulf in expectations and experiences of leadership. Whilst it should be noted that there is no evidence to suggest that these negative assessments are reflective of the actual skills/qualities of senior leaders (indeed it is quite possible that many of these people are amongst those who rated their own capacity moderately highly) it highlights a significant issue to which senior leaders would be advised to pay attention.

Reclaiming Leadership in Higher Education

Follower-centric perspectives on leadership stress the importance of building strong relationships between leaders and followers that are founded on trust, respect, and a shared sense of purpose. The evidence outlined above suggests that this is not the experience of many people currently working in HE — a situation that has significant implications for the sector.

If we continue along the current trajectory the chances are that HE may slip into terminal decline (Fleming, 2021). A chasm between the values and priorities of those in formal leadership and management roles and those of academics involved in teaching, research, and/or external engagement will lead to further disillusionment with the academic profession and a corresponding deterioration in the quality and significance of academic work. This is a trend that has been well documented in critiques of neoliberalism and new public management in universities. So, what might we as academics (with or without management responsibilities) do to improve the situation?

First, we should acknowledge our rights and responsibilities as “citizens of the academic community” (Bolden et al., 2014) to play an active role in the governance of our HE institutions and the wider sector. Disengagement, whilst understandable, leaves space and opportunities for toxic management to thrive and may render us complicit in the process.

Second, as part of this we would do well to create and sustain spaces for critical and constructive debate around the nature and purpose(s) of HE in contemporary society. Whilst this should allude to and promote core values (such as academic freedom) it should also engage with the very real challenges facing many universities around financial sustainability and market position. Only through an honest and open dialogue can we hope to transcend the current fractures that characterize the sector.

Third, we need to ensure that a plurality of voices, perspectives, and lived experience infuse HE policy and practice. Genuine inclusion needs to be put at the heart of the educational mission of universities and used as a driver for continuity and/or change within the sector (see Bolden et al., 2019 for a similar argument about healthcare).

Fourth, we should rebuild our sense of community — to develop human relationships that have been fractured during the COVID pandemic, to mentor and support one another, and to celebrate collegiality and collective endeavour.

And fifth, we should find ways of (re)energizing and (re)inspiring current and future academics to embrace the privilege and opportunities of working in a sector that has such a huge impact on the lives of so many. Education and research are vehicles for individual and collective transformation and change and are the primary mechanisms through which we are likely to address global challenges such as climate change.

In relation to the last of these I was inspired by a recent LinkedIn post by colleague that reiterated his passion for the job (see below). As we reflect on the year that’s passed and consider the year ahead, I urge each of us to think on what WE can do and how, in our own (small) way, we can reclaim our role(s) and responsibilities as leaders in higher education.

Another term draws to a close 🌱

Each year, as September rolls around I always find myself thinking "I hope that I still love teaching and learning as much this year". The sign that I finish off the term being simultaneously proud of students; grateful for the opportunity to be a small part of their journey; inspired by conversations; excited by the content; and sad for it to be over is a good one.

It's no doubt that our world faces multiple crises, and that will continue, but being in this environment fills me with hope that generations want to understand what is happening in our landscape and want to put good into the world. Spending the time to delve into the human condition and understand new possibilities is what university is all about, and why I love this job.

So - here's to accepting the feeling of sadness as a term draws to a close, but hope for what comes next 🌱

Dr Neil Sutherland, LinkedIn - 13 December 2023 [Reproduced with author’s permission]

References

Albert, S., & Whetten, D.A. (1985). Organizational Identity. In L.L. Cummings & M.M. Staw (Eds), Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 7 (pp. 263‒295). JAI Press.

Bolden, R., Gosling, J., & O’Brien, A. (2014). Citizens of the Academic Community: A Societal Perspective on Leadership in UK Higher Education. Studies in Higher Education, 39(5), 754-770. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.754855

Bolden, R., Adelaine, A., Warren, S., Gulati, A., Conley, H., & Jarvis, C. (2019) Inclusion: The DNA of Leadership and Change. UWE, Bristol on behalf of NHS Leadership Academy, Leeds. https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/852067/inclusion-the-dna-of-leadership-and-change

Fleming, P. (2021) Dark Academia: How Universities Die. Pluto Press.

Gronn, P. (2003). Leadership: Who Needs It? School Leadership & Management, 23(3), 267-291. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363243032000112784

Jenkins, S. (2023, February 6). British Universities Can No Longer Financially Depend on Foreign Students. They Must Reform to Survive. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jun/02/british-universities-foreign-students-deficits-government-higher-education

Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A., & Hopkins. D. (2006). Successful School Leadership What It Is and How It Influences Pupil Learning. National College for School Leadership. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/6617/2/media-3f6-2b-what-we-know-about-school-leadership-full-report.pdf

Macfalane, B., Bolden, R., & Watermeyer, R. (2024) [Forthcoming]. Three Perspectives on Leadership in Higher Education: Traditionalist, Reformist and Pragmatist. Higher Education. https://link.springer.com/journal/10734

Neves, J., & Parkin, D. (2023). Leadership Survey for Higher Education. Advance HE. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/leadership-survey-higher-education

Ospina, S.M., Foldy, E.G., Fairhurst, G.T., & Jackson, B. (2020). Collective Dimensions of Leadership: Connecting Theory and Method. Human Relations, 73(4), 442-463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719899714

PWC. (2021). Global Crisis Survey 2021: Building Resilience for the Future. PWC Research. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/crisis-solutions/global-crisis-survey-2021.html

Ross, J. (2022, July 8). ‘Do It All’ Culture ‘Driving Great Resignation’ in Academia. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/do-it-all-culture-driving-great-resignation-academia

Smith, W.K., Lewis, M.W., & Tushman, M.L. (2016). ‘Both/And’ Leadership. Harvard Business Review, 94(5), 66-70. https://hbr.org/2016/05/both-and-leadership

Spillane, J.P., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J.B. (2004). Towards a Theory of Leadership Practice: A Distributed Perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(1), 3-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000106726

Uhl-Bien, M. (2021). Complexity Leadership and Followership: Changed Leadership in a Changed World. Journal of Change Management, 21(2), 144-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.1917490

Watermeyer, R., Bolden, R., Knight, C., & Holm, J. (2022). Leadership in Global Higher Education: Findings From a Scoping Study. Advance HE. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/leadership-global-higher-education-findings-scoping-study

Watermeyer, R., Shankar, K., Crick, T., Knight, C., McGaughey, F., Hardman, J., Suri, V., Chung, R., & Phelan, D. (2021). ‘Pandemia’: A Reckoning of UK Universities’ Corporate Response to COVID-19 and Its Academic Fallout. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 42(5-6), 651-666. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2021.1937058

Winter, R.P., & O’Donohue, W. (2012). Academic Identity Tensions in the Public University: Which Values Really Matter? Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 34(6), 565-573. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2012.716005

Dr. Richard Bolden is Professor of Leadership and Management and Director of Bristol Leadership and Change Centre at Bristol Business School, University of the West of England. His teaching and research explore the interface between individual and collective approaches to leadership and leadership development. He has published widely on topics including distributed, shared and systems leadership; leadership paradoxes and complexity; cross-cultural leadership; and leadership and change in healthcare and higher education. He is Associate Editor of the journal Leadership, Fellow of the International Leadership Association, Visiting Professor at the University of Pretoria and Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. His latest book Exploring Leadership: Individual, organizational and societal perspectives, 2nd edition was published by Oxford University Press in March 2023.

If you find these reflections to be of value in your work and life, please consider becoming part of ILA’s leadership community.

As an Amazon Affiliate ILA may earn a small amount from qualifying purchases (at no extra charge to you) when you click on a link to a book above. Thank you for your support!