by Dr. Karen L. Stout

- 6 October 2023

Share this article:

Note: Student leaders involved in this program are able to attend the International Leadership Association Global Conference in 2023 through a grant provided by the Sustainability, Equity, & Justice Fund at WWU.

The Importance of Cultivating Leadership for a Thriving Future Now: A Member Spotlight on the Leadership Studies Community Engagement Program, Morse Leadership Institute, Western Washington University

People are aware that they cannot continue in the same old way but are immobilized because they cannot imagine an alternative. We need a vision that recognizes that we are at one of the great turning points in human history when the survival of our planet and the restoration of our humanity require a great sea change in our ecological, economic, political, and spiritual values.

~ Grace Lee Boggs

Many have called for a change in how we view and teach leadership, particularly highlighting the long-term impact of our work. The International Leadership Association’s 25th Global Conference theme statement and call for proposals asks us to consider how to develop and sustain systems that contribute to thriving, thereby shifting the emphasis from the leader to the community as a whole. In the Morse Leadership Institute (MLI) at Western Washington University (WWU), a mid-sized regional master’s granting public university in the Pacific Northwest of the United States, we’re trying to do exactly that. We’ve configured our introductory course and peer leadership program to embrace the principles of critical leadership studies by engaging students in community service projects while also focusing on wellbeing. We help students understand and explore their agency through critical leadership lenses in our structured peer mentoring program, which is led by a leadership team.

Several bodies of knowledge inform our work. Our applied leadership learning opportunities are based on the human-centered design approaches perfected by Purdue University’s EPICS program (Zoltowski & Oakes, 2014), but we specifically tie our projects to the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (https://sdgs.un.org/goals). The Okanagan Charter, created by the University of British Columbia, informs our decision-making, practices, and expectations for all involved in the program by focusing on wellbeing and community care (https://wellbeing.ubc.ca/okanagan-charter). But our primary curriculum is that of critical leadership studies and leadership skill development.

Calls for Change

Leadership, agency, privilege, access to resources, and power are inextricably bound and need to be front and center in our conversations about leadership with our students. Dugan and Humbles (2018) call on us to recognize “the radical importance of now” in leadership development education because of the glaring “gap between what we say we value in leadership education and how we translate those values into practice” (p. 10).

Kellerman (2018) highlights that as leadership education programs have expanded over time, so, too, has the demand for ethical leaders. Yet authoritarianism is increasingly valued at local, national, and global political levels. Many approaches to leadership education rely on emphasizing how individuals — usually charismatic, White men — set visions that followers are expected to embrace (Collinson & Tourish, 2015; Jimenez-Luque, 2021a & 2021b; Sinclair, 2007; Trimble & Chin, 2019), yet scholars have revealed that understanding Indigenous and global perspectives can improve leadership education (Chin & Trimble, 2015; Jimenez-Luque, 2021a & 2021b; Jimenez-Luque & Trimble, 2021; Sinclair, 2007; Trimble & Chin, 2019).

How then are diverse and contextually relevant leadership styles to gain the respect and action they deserve?… [It] requires paradigm shifts in our theories of leadership that examine and incorporate the ways diversity shapes our understanding of leadership and its effects. (Trimble & Chin, 2019, p. e1)

Given the current college-aged generation’s exposure to social media and constant barrages of local and global information (that often demonstrates economic, social, and political power imbalances) our students are capable and savvy enough to embrace these concepts in an introductory level course; but we must be careful with how we engage in such work, so as not to perpetuate problematic systems, behaviors, messages, and ideas.

Program Design Inspiration

I began the redesign of the MLI Community Engagement Program (CEP) program with direct inspiration from Purdue University’s Engineering Projects in Community Service (EPICS) program (described by Zoltowski & Oakes, 2014, as well as others). This multidisciplinary program introduces students to engineering through community engagement projects, which builds communication and leadership skills, and offers a minor in Leadership Studies. This nearly 30-year-old program serves over 800 students per year at Purdue and has increased diversity within college and pre-college engineering levels. Non-engineering programs have implemented similar programs with success. “The EPICS model has proven to be effective as a curricular model… [and also as] a means to develop and sustain long-term community partnerships that provide mutual benefit and significant community impact” (p. 27).

Further, we embrace the Okanagan Charter (2015), created by the University of British Columbia and agreed upon by 45+ institutions (https://wellbeing.ubc.ca/okanagan-charter). WWU has signed onto the charter, which calls WWU to systemically embed and promote health and wellbeing in all levels of university decision-making and operations. For the MLI, this means we periodically devote time to address health and wellbeing issues (e.g., sleep hygiene, nutrition, interpersonal relations, conflict management lessons) in leadership classes, events, and trainings. It also means we reserve time for personal check-ins and provide multiple mechanisms for anonymous feedback.

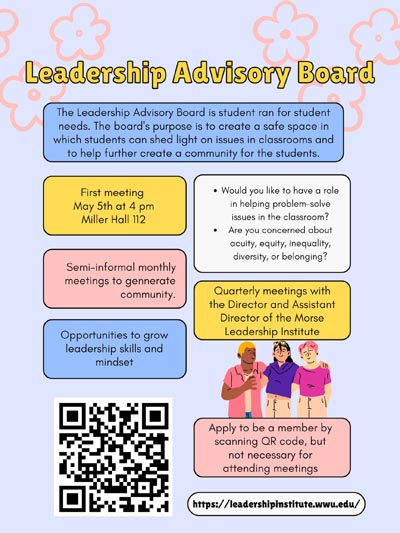

In keeping with the precepts of critical leadership studies, as director I have also asked students who are declared leadership studies minors to create an advisory board for MLI. The idea is to provide me with regular and direct feedback regarding health and wellbeing; access; diversity; equity, inclusion and belonging issues; power imbalances, or experiences of toxicity. We want to know if problematic or toxic communication or behavior is taking place in our spaces to address these issues sooner rather than later. While we expect our student leaders to demonstrate inclusive and ethical leadership, we know students need to be trained and supported by institutional structures and processes that are equitable and just. To this end, MLI provides curriculum and courses on conflict resolution and mediation, and we hold and role model difficult conversations to deescalate conflict.

While we’re not far in this work yet, our hope is that by working directly with students to create a community of wellbeing, we can provide an opportunity for student governance, which informs faculty performance and governance, resulting in more effective and caring pedagogy.

Our community engagement projects overtly embrace the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (https://sdgs.un.org/goals). The MLI is a part of a collective of similar all-university programs (housed in the Provost’s Office, not in a traditional university college) where several programs have decided to emphasize these 17 goals. As a result, MLI now offers a Climate Leadership Certificate in combination with the Sustainability Engagement Institute at WWU. This aligns with WWU’s longstanding commitment to the environment, as evidenced by its 1969 creation of the first environmental college at a U.S. institution of higher education. Our hope is to cultivate and connect student leadership locally and globally in a way that demonstrates a commitment to social justice and health for all (including a sustainable planet), which provides an opportunity for growth, reconciliation, and healing.

We can begin by doing small things at the local level, like planting community gardens or looking out for our neighbors. That is how change takes place in living systems, not from above but from within, from many local actions occurring simultaneously. ~ Grace Lee Boggs

Program Description

The MLI’s CEP is comprised of a series of courses — LDST 101, 450, 451, and 452 — ranging from 3 to 5 credits. The 101 course (a general university requirement) is structured to meet three times a week; twice in large lecture (~60 students) taught by either the institute director or associate director (with graduate student assistance), and once in “discussion sections” where smaller groups of students (~14-16 each) are facilitated by more-advanced leadership studies students enrolled in LDST 450, 451, or 452 (depending on student goals and progress). Discussion Section Facilitators (or “DSFs”) and undergraduate Teaching Assistants (“TAs”) work collaboratively with graduate students, the MLI associate director, and director as the “Leadership Team.” Students enrolled in the 400-level courses have their own similar, but more advanced curriculum designed to support their development through their role as peer mentors for LDST 101 students.

The curriculum for all these courses first addresses concepts like social location, privilege, power, stocks of knowledge, and agency. We encourage students to learn about and reflect on marginalization, exclusion, oppression, and the power of inclusive leadership. We adapt ideas from the early chapters of Dugan’s (2017) text to make them appropriate for an introductory-level course by then scaffolding it with more advanced curriculum if students continue through our program. We bring in outside readings to provide examples of concepts that affect or reflect students’ diverse lives and experiences. Through this pedagogy, our students are exposed to and must learn about the cultures and contexts in which they are immersed (Collinson & Tourish, 2015, p. 583). By engaging in messy, sometimes conflictual, complicated processes, they rethink leadership and followership, critique their romanticized perceptions of leadership, and witness how power is foregrounded in cultural and institutional structures (Collinson & Tourish, 2015). The community engagement projects provide them opportunities to observe these concepts, which play out in the human experience, as students develop, create, reinvent avenues for change.

Seemiller’s (2019) text Discovering the Leader Within inspired our skill development questions for students to connect their applied leadership learning to the CEPs. Students answer questions and surveys on Canvas (our learning management system) designed to reflect the leadership competencies, skills, and outcomes (Seemiller, 2014) we’ve chosen to emphasize in MLI. Written and verbal reflective exercises, whether for individual, small, or large groups, help students develop meaningful, personal connections with the leadership concepts we’re learning. From confronting privilege and savior complexes when serving others, to finding intrinsic value in those who may be unknown to or different from us, to recognizing the struggles or privileges within ourselves when we witness the struggles and privileges of others, our students exhibit demonstrable leadership growth by engaging in these projects. Through collectively working together on a small solution to a local problem tied to larger global issues, students are given an opportunity to reflect on their role in how societal and institutional structures can be changed for long-term solutions.

Each discussion section engages in a different community project that aims to serve the underserved “unexotic underclass,” which exposes students to current issues of institutional and environmental racism and classism, as well as other complex societal issues (Martin, 2016). For some students, issues of poverty, food, or housing insecurity directly impact or has impacted their lives. For others, it’s enlightening and infuriating to learn of the challenges their peers and others face. “While thousands of the country’s best and brightest flock to far-flung places to ease unfamiliar suffering and tackle foreign dysfunction, we’ve got plenty of domestic need” (Martin, 2016, np). We are currently running 4 class projects:

Restoring the Nooksack River

Inspired by a WWU professor whose research indicates the river is in “grave danger” (Kempe, 2022), the Nooksack is crucial to economic and environmental livelihood in Whatcom County, which is the number one producer of red raspberries for the world, the county with the largest agricultural market value in the state (https://whatcomfamilyfarmers.org/2019/02/27/whatcom-farm-facts/), and an important spawning habitat for Pacific Ocean salmon. Our student group often supports the Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association by volunteering at tree-planting or invasive species abatement cleanups.

Menstrual Health Advocacy

This partnership with Days for Girls, International works to end “period poverty,” or the lack of access to menstrual hygiene products, which affects education and life-long employability for a significant portion of the world’s population. Estimates are that half a billion people do not have the products they need on a monthly basis, which affects wealthy nations just as much as developing ones (Michel, Mettler, Schönberger, & Gunz, 2022). This group educates about period poverty, fundraises for, and distributes reusable, sustainable menstrual hygiene products.

Mental Health Advocacy

Access, affordability, awareness, and stigma are some of the barriers for obtaining mental health services. This group supports WWU counseling services and our campus farm to offer gardening and farming activities for students on campus through peer mentoring models.

LGBTQIA+ Advocacy

Research demonstrates that LGBTQIA+ individuals are at risk for homelessness, poverty, crime, and trauma. As WWU is located near an international border, our area has a significant homeless population with many LGBTQIA+ young people served by only a few agencies. We’ve supported local non-profits but have found they often don’t have the capacity to accept our help (in the form of student learners on the quarter system), so we’ve turned to raising funds and awareness for WWU programs, like buying gender-affirming clothes for transgender or non-binary students.

This service-learning based pedagogy is a heavy workload (we feel with greater educational payoff), so we scaled back the size of our classes to accommodate the complexity of the work until we feel assured of the strength and training of our curriculum. Yearly, this program serves ~325 students with hundreds more supported through other classes, student clubs and government, participation in other interdisciplinary minors and certificates, and the execution of university and community events; ~25 Leadership Studies minors graduate from WWU per year. As we solidify curriculum for the program, strengthen our training of student leaders, and clarify their responsibilities, we engage in this work collaboratively and iteratively, improving quality on a quarterly basis. Our hope is to add 1-2 additional discussion sections by the end of this year.

The Program’s Impact

While the Leadership Studies minor at WWU is only 8 years old and has only graduated ~200 students, our overall students’ persistence and graduation rate is 98.91% — the university’s best (albeit with a small sample size). We are collecting more data this year to assess our program’s impact, but so far, especially with narrative testimony, we’re accomplishing our goals. One of our minors, Jaxon Frodesen, said:

I chose WWU specifically for the Leadership minor because it is the only state school I knew about with this kind of a program. Not many students realize the kinds of opportunities that this minor can provide because it’s still fairly small, but I’ve been involved with the Morse Institute for a couple of short years and everyone I’ve met within the program strives to make this school and community a better place for everyone. That’s the kind of learning environment I knew I wanted to be a part of.

By shifting toward a collaborative and transparent decision-making and authority model and by creating a basic student shared governance system with direct lines of communication to institute leadership, it (hopefully) ensures better decision-making and makes space to address ADEIB and wellbeing concerns. Our hope is that “[knowing] what goes on outside actually can affect (and sometimes powerfully support) the work of trying to create and sustain an inclusive space inside” (emphasis original, Armstrong, 2011, p. 59).

These strategic investments in the growth and development of the program have also resulted in other positive outcomes. Our focus on the UN SDGs along with health and wellness resulted in the MLI receiving a $35,000 grant from the Sustainability, Equity, & Justice Fund at WWU.

Want to see for yourself?

MLI is bringing our leadership team and several students to ILA’s 25th Global Conference. A small group of our students will also represent the Institute in the Undergraduate Division of the International Student Case Competition. They will also attend our reception (you’re invited!) on Friday, October 13th and will present with us about the program on a panel Saturday, October 14th. Please come!

As Eckhart Tolle said, “The power for creating a better future is contained in the present moment; You create a good future by creating a good present.” Thus, we hope that the time and effort we invest in contributing to our students’ wellbeing and their ability to face the leadership challenges of the community engagement projects in supportive ways nurtures them into being successful future leaders.

Keywords: Critical leadership studies, peer mentoring, leadership education, leadership development. United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, The Okanagan Charter, Engineering Projects in Community Service (EPICS), service-learning.

References

Armstrong, M.A. (2011). Small world: Crafting an inclusive classroom (no matter what you teach). Thought & Action, Fall, 51-61.

Chin, J.L. & Trimble, J.E. (2015). Diversity and Leadership. Sage.

Collinson, D., & Tourish, D. (2015). Teaching leadership critically: New directions for leadership pedagogy. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(4), 576-594.

Dugan, J.P. (2017). Leadership Theory: Cultivating Critical Perspectives Studies. Jossey-Bass.

Dugan, J.P., & Humbles, A.D. (2018). A paradigm shift in leadership education: Integrating critical perspectives in leadership development. New Directions for Student Leadership, 159 (Fall), 9-26. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20294

Jimenez-Luque, A. (2021a). Decolonial leadership for cultural resistance and social change: Challenging the social order through the struggle of identity. Leadership, 17(2), 154-172.

Jimenez-Luque, A. (2021b). Redefining leadership through the commons: An overview of two processes of meaning-making and collective action in Barcelona.” In D.P. Singh, R.J. Thompson, & K.A. Curran (Eds.) Reimagining leadership for a more ethical, equitable, and just world (pp. 81-95). Emerald.

Jimenez-Luque, A., & Trimble, J.E. (2021, November 4). Peace leadership and cultural diversity consideration for our common future. In A. Jimenez-Luque, G. Skawen:nio Morse, and J.E. Trimble (Eds.), Global & Culturally Diverse Leadership in the 21st Century Column of Interface Newsletter. International Leadership Association. https://intersections.ilamembers.org/member-benefit-access/interface/global-and-culturally-diverse-leadership/2021-common-future

Kellerman, B. (2018). Professionalizing Leadership. Oxford Press.

Kempe, Y. (2022, February 2). The Nooksack river is in “grave danger,” warns Whatcom scientist with numbers to back it up. Bellingham Herald. https://www.bellinghamherald.com/news/local/article257231682.html

Martin, C. (2016). The reductive seduction of other people’s problems. Bright Magazine (January 11) https://brightthemag.com/the-reductive-seduction-of-other-people-s-problems-3c07b307732d

Michel, J., Mettler, A., Schönenberger, S., Gunz, D. (2022). Period poverty: Why it should be everybody’s business, Journal of Global Health Reports, 6, np. https://doi.org/10.29392/001c.32436

Seemiller, C. (2014). The Student Leadership Competencies Guidebook. Jossey-Bass.

Seemiller, C. (2019). Discovering the Leader Within: Self-Leadership Skills for Teens. LeadU.

Sinclair, A. (2007). Leadership for the disillusioned. Allen & Unwin.

Trimble, J.E., & Chin, J.L. (2019). Exploring culturally diverse leadership styles: A mindset and multicultural journey. Social Behavior Research and Practice, 4(1), e1-e2. https://doi.org/10.17140/SBRPOJ-4-e005

Zoltowski, C.B., & Oakes, W.C. (2014). Learning by doing: Reflections of the EPICS program. International Journal for Service-Learning in Engineering Special Edition, Fall, 1-32. https://doi.org/10.24908/ijsle.v0i0.5540

About Dr. Karen Stout

Karen Stout, Ph.D. is a Professor of Communication Studies, the Bowman Distinguished Professor of Leadership, and Director of the Morse Leadership Institute at Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington, United States of America. Dr. Karen Stout’s scholarship explores marginalization and exclusion in workplaces and social groups, women’s leadership, service-learning pedagogy, and other scholarly teaching and learning concerns. While she took over leadership of the LDST 101 program from a scholar (Dr. Joseph Garcia) well-versed in critical leadership studies, she’s the primary creator of the current incarnation of this multi-level program by bringing together the literature and pedagogy. She’s grateful for the assistance of her talented student leaders, former staff, and new associate director (Dr. Holly Diaz) in helping the program fulfill its potential.

Correspondence can be directed to the author at Western Washington University, the Morse Leadership Institute – MS 9128, 516 High Street, Bellingham, WA 98226, at Karen.Stout@wwu.edu, or 360-650-2563.