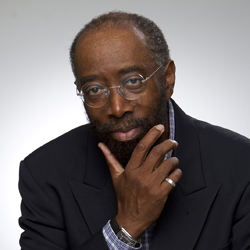

by Errol A. Gibbs

8 September 2020

Share this article:

Leadership today seems to fulcrum around political, economic, and organizational objectives, more so than crucial humanitarian objectives. Leaders in the public and private sphere find themselves in an unusual and precarious position as the COVID-19 pandemic (medical crisis) precipitated the global economic crisis of 2020, unlike the footprint of other disasters that begin with a financial dilemma and then later reveal the personal and societal consequences.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to attention the humanitarian costs, particularly the plight of the elderly and people of color, particularly Blacks, with pre-disposed signature illnesses such as diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, heart disease, and kidney disease, and Indigenous peoples. Compounding this epoch-making event was the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, a 46-year-old Black American male in Minneapolis, Minnesota, during an arrest for allegedly using a counterfeit bill. These challenges opened fissures in the black-white racial divide resulting in unprecedented responses by people of all “races,” color, cultures, and beliefs. Masses of people took to the streets in protest marches – worldwide, in what global watchers refer to as a historical turning point.

These recent incidents have caused citizens worldwide to view leadership as enigmatic. Many question the approach of their leaders, their competencies, and the nature of their responses to problems1 that are complex and multi-layered. They challenge the concepts of leadership that seem to lack an informed balance between “economic” and “humanistic” needs and interests, underpinned by the fear of the collapse of the economy (the Stock Market). Paradoxically, this dichotomy between the economy and humanity underpin the current questioning of the obligations of leadership.

Many citizens assume that leadership qualities are integral to a leader’s position of power, election to an office, or personal attributes – erudition, charisma, or courage. They believe that the nature of these appointments and election to office entails leadership capabilities. The moral considerations of leadership may not be a central criterion in the leadership equation. Downplaying this aspect may exclude the selection of leaders with the vital 360-degree vision.

Some leaders stake their popularity in the postmodern stock market economy. They may not perceive the complexities of an interconnected world, where race, color, culture, religion, self-interest, and nationalism are becoming more pervasive ―nationally and internationally. The phenomenon of the “Global Village” has become a misnomer, underpinned mainly by digital connectivity, and corporate trans-globalism ―the movement of goods and services.

Moreover, the electorate and stock shareholders have accepted the stock market’s performance as the measure of their leaders’ success. Leading corporations to layoff masses of employees as the “counterbalance” to economic downturns. Governmental intervention through corporate tax cuts and corporate bailouts undergird this view of leadership acumen. These strategies enable corporate leaders to demonstrate financial viability as symbolic of their leadership insight without tapping into capital markets or corporate reserves.

These leadership models serve the “shareholder interest” as the primacy of corporate survival at the stakeholder’s expense we – the public interest. Herein lies a double-edged sword that suffocates the “greater good” of leadership. Government and corporate leaders rely on the stock market index as the barometer of their leadership effectiveness. The evening news tout the stock market index, undergirded by gross domestic product (GDP) and gross national product (GNP), as evidence of economic stability and/or economic boon.

Times of crisis test the validity, the assumptions, and the acceptance of these frameworks of leadership assignments when leaders face insurmountable challenges. Leaders may not be directly responsible for the social and economic upheavals in their countries. However, a more vital measure of the “true” social and economic progress of countries are indicators on the Gini index or Gini coefficient (Corrado Gini 1912).

Times of crisis test the validity, the assumptions, and the acceptance of these frameworks of leadership assignments when leaders face insurmountable challenges.

The Gini index measures the extent to which the distribution of income (or, in some cases, consumption expenditure) among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. In real-time, real-life situations bring these deviations to light when catastrophic events like COVID-19 befall a country. The creation of such equitable societies requires significant investments in people and infrastructure, which ultimately benefits the macro and micro-economies. Leadership, therefore, is an intricate balance between the economy and humanity.

In summary, positions of elected authority play a part in leadership, but the appointment may not always weigh heavily on important leadership criteria, such as defining the vision, mission, goals, and objectives. Likewise, to direct, motivate, teach, listen, encourage, participate, mentor, and reward their followers. Furthermore, leadership is about the exercise of “civic duty” undergirded by “moral duty.” It is a way of life and led by example. Servanthood leaders provide unwavering service to those who follow – they consider human factors such as color, race, culture, language, religion, nationality, and social and economic existence.

These leaders make available equitable opportunities for human growth and development. They seek the highest ideals for creating a just society. Historical evidence of unprecedented calamities, either humanly inspired, humanly caused, or naturally occurring, calls for a new form of capitalism undergirded by egalitarianism or equalitarianism. The COVID-19 pandemic could be the turning point to introduce these new principles of leadership. This new approach to leadership will stabilize nations and the world economies – characterized by equal worth and moral dignity for human sovereignty.

1The book, Poor Leadership and Bad Governance, edited by Helms, Ludger, (2012), provides a chronology of “wicked problems” facing leaders in our postmodern era.

Errol A. Gibbs is a former Project Management and Business Process Re-engineering Analyst, Senior Process Designer, and Planning and Scheduling Engineer Officer. He is a self-inspired researcher, writer, speaker, philosopher, mentor, and moderator. He writes for the Toronto Caribbean (TC) Newspaper, under the banner “Philosophically Speaking.” His books include Five Foundations of Human Development (FFHD) (2011) and Discovering Your Optimum Happiness Index (OHI) (2016). A sample of his position papers include A Black Empowerment Manifesto (2020) and a Manufacturing Engineering Project Office: A Critical Link to Supply Chain Integration (2000). Errol prides his relationship with the ILA: “The organization has the ‘faculty of knowledge’ to be at the forefront of the global leadership debate.”