by Richard Bolden

19 January 2022

Share:

“In reality they all lived in a kind of hieroglyphic world, where the real thing was never said or done or even thought, but only represented by a set of arbitrary signs.” Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence, 1920

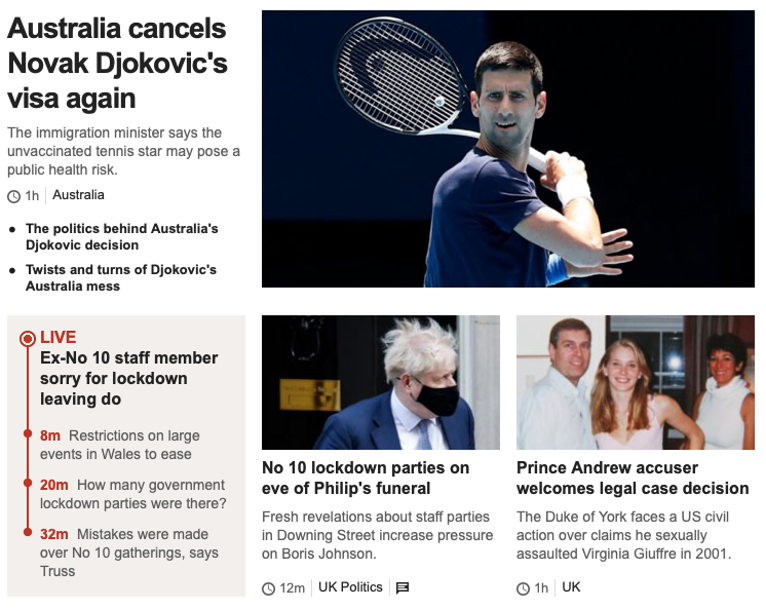

Over the past few weeks, a series of stories have dominated news headlines around the world that, whilst in different contexts, bear a number of striking similarities.

The first of these concerns revelations about a string of parties hosted at 10 Downing Street during the pandemic. Whilst Prime Minister Boris Johnson has consistently attempted to deflect allegations and blame, arguing that these were work events and that Covid restrictions were followed at all times, the public and indeed his own party have become increasingly frustrated by his unwillingness to apologize and take responsibility, and by his apparent disregard for the rules that he and colleagues had imposed across the country.

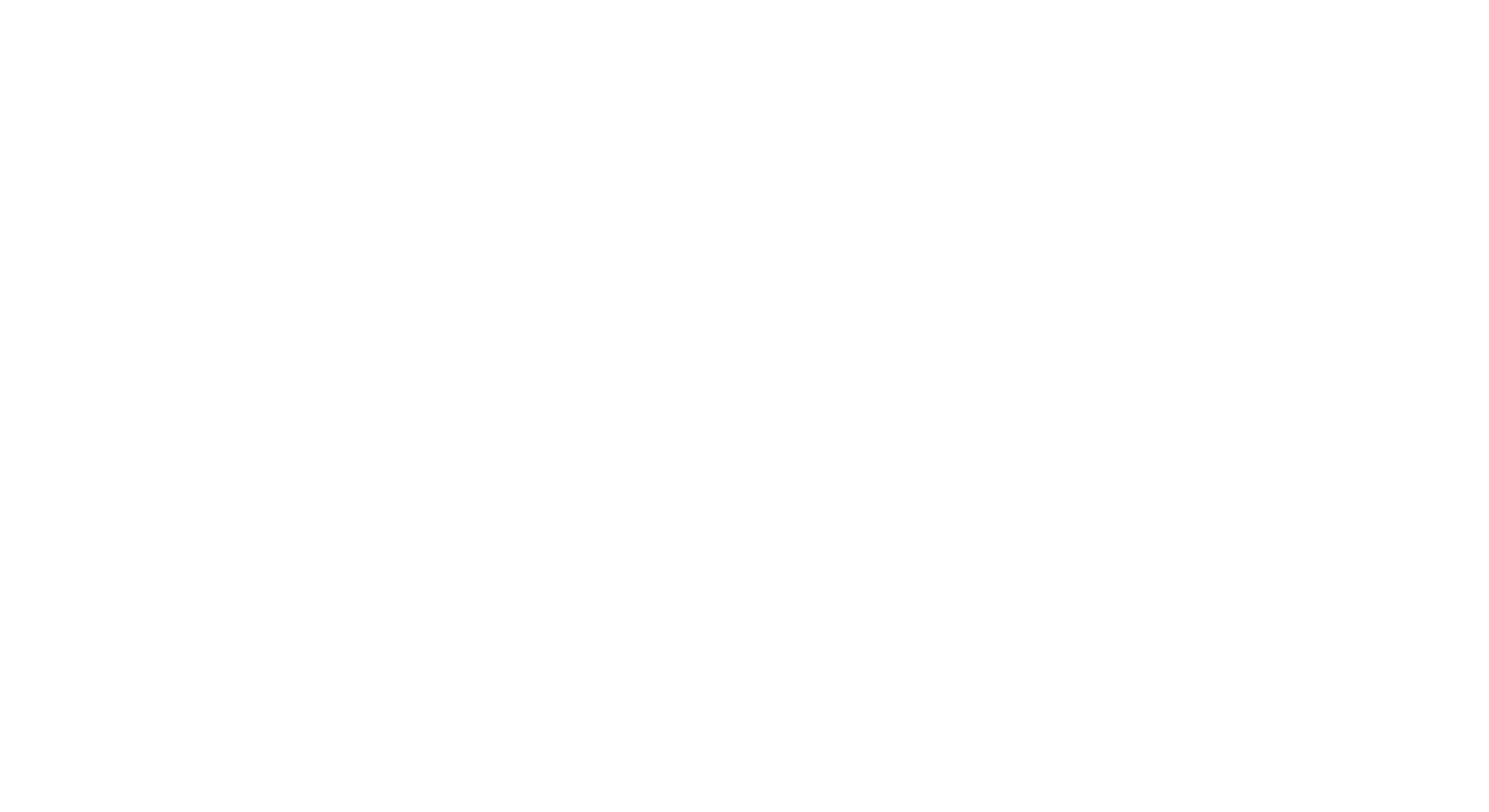

The second regards the ability of unvaccinated tennis star Novak Djokovic to enter Australia to play in the Australian Open. For Djokovic this would have enabled him not only to defend his title but also to potentially achieve the highest ever number of Grand Slam titles in men’s tennis. His Visa application, however, was contested on the basis of him breaching Australian Immigration rules around COVID vaccination status, as well as an error in the reporting of prior travel on his Visa form.

And the third relates to whether or not Prince Andrew will face trial for alleged illegal sexual activity. Needless to say, the Prince has consistently denied these allegations — publicly stating that he’d never met his accuser (despite photographic evidence to the contrary) and even taking part in a televised interview where he endorsed his position by stating that he was “unable to sweat” and was picking up his daughter from a pizza restaurant on the evening of one of the suggested incidents (despite no substantive evidence to support either claim).

Headlines on the BBC News website, at 11:00 on 14/01/2022

Despite their obvious differences, what each of these stories has in common is the sense that people in positions of power and influence believe that they are free to operate beyond the rules that govern the ways that others are expected to live their lives.

These stories have been widely reported, not just in mainstream media but also through the internet and on social media where each has fuelled a storm of opinion and memes. Despite their obvious differences, what each of these stories has in common is the sense that people in positions of power and influence believe that they are free to operate beyond the rules that govern the ways that others are expected to live their lives. Whilst these are just the latest in a long history of examples of privilege and inequality, what is notable this time is the turning tide of public opinion. Whilst there remain those that support and defend the protagonists, our collective willingness to forgive and forget is in rapid decline. In each case people are frustrated not just by the incidents themselves but by the lack of respect that the continued avoidance of accountability demonstrates. Trust has been broken and, whatever the outcome of any of these sagas, will be difficult to rebuild — not just for the individuals themselves but also the institutions they represent.

Together, these cases illustrate the reciprocal and relational nature of leadership. As Professor Joanne Ciulla argues: “Leadership is not a person or a position. It is a complex moral relationship between people, based on trust, obligation, commitment, emotion, and a shared vision of the good” (Ciulla, 1998, p. xv). In each of these examples the moral foundation of these individuals (and their institutions) has been brought into question, which erodes their credibility, authority, and ability to influence others.

Linked to this is the sense of one set of rules for them and another set of rules for the rest of us. A fundamental premise of the social identity approach is that leaders must demonstrate that “we’re in this together.” Professor Stephen Reicher and colleagues have spoken particularly about the need for identity-based leadership through the pandemic and highlighted the consequences of failing to do so (Jetten et al., 2020). The (post) pandemic situation is particularly pertinent in the cases of Boris Johnson and Novak Djokovic where the tough lockdown conditions and personal loss endured by populations in the UK and Australia make breaches of the regulations — and the apparently dismissive ways in which they have been responded to — particularly egregious.

These cases also highlight the complex, systemic nature of leadership and the need to focus attention on small details as well as broader patterns (French & Simpson, 2014). Whilst Boris Johnson, for example, may have weathered many a storm during his career, an overt breach of Covid regulations may well be enough to unseat him from his position in parliament (much as it has for others in the government). For Djokovic, a failure to complete his Visa application correctly has ended his ambitions to win the 2022 Australian Open. And whilst not wishing to defend his actions, differences between legal systems in the UK and USA may have contributed to Prince Andrew being indictable for alleged crimes in New York.

Overall, these stories demonstrate shifting social trends around our relationship with and deference towards people in positions of power and authority. Whilst I believe we are still far from a world of “post-heroic leadership,” our collective tolerance for people who appear arrogant or elitist appears to be waning. As leadership scholars, educators, and practitioners, however, we must also be careful not to be drawn in the polarizing vortex of opinion that such stories fuel. Whilst these particular examples may be playing out in public view — exposing the sordid intricacies for all to see — we must also remain alert for the stories that remain hidden from view. On the day that I am writing this article, for example, the journalist Carole Cadwalladr is appearing in the U.K. High Court to defend her decision to publish and share her account of the ways in which she believes Trump, Farage, Banks, and others used Facebook to spread misinformation to influence the outcome of Brexit vote. (For further details see her gofundme page and TED talk). Such cases are risky and expensive. Yet, unless people are willing to speak-up, we may find democracy slipping away.

I began this article with a quote from Edith Wharton’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Age of Innocence, which highlighted the tensions and ambiguities within a world undergoing social and political change. There are many that would argue we are at a similar turning point in history — facing the combined challenges of COVID-19, climate change, and social inequality that call for a reappraisal of who “we” are, what “we” stand for and who “we” are willing to follow. In the words of Wharton, if we are not content with the answers that we find, then we have the capacity to redraw the boundaries within which we find ourselves.

“Who’s ‘they’? Why don’t you all get together and be ‘they’ yourselves?” Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence, 1920

References

Ciulla, J. B. (Ed.). (1998). Ethics: The Heart of Leadership. Quorum.

Jetten, J., Reicher, S., Haslam, S.A., & Crowys, T. (2020). Together Apart: The Psychology of COVID-19. Sage.

French, R., & Simpson, P. (2014). Attention, Cooperation, Purpose: An approach to working in groups using insights from Wilfred Bion. Routledge.

Dr. Richard Bolden has been Professor of Leadership and Management and Director of Bristol Leadership and Change Centre at Bristol Business School, University of the West of England (UWE) since 2013. Prior to this he worked at the Centre for Leadership Studies at the University of Exeter Business School for over a decade and has also worked as an independent consultant, research psychologist and in software development in the UK and overseas.

His research explores the interface between individual and collective approaches to leadership and leadership development in a range of sectors, including higher education, healthcare and public services. He has published widely on topics including distributed, shared and systems leadership; leadership paradoxes and complexity; cross-cultural leadership; and leadership and change. He is Associate Editor of the journal Leadership.

Richard has secured funded research and evaluation projects for organisations including the NHS Leadership Academy, Public Health England, Leadership Foundation for Higher Education, Singapore Civil Service College and Bristol Golden Key and regularly engages with external organisations.